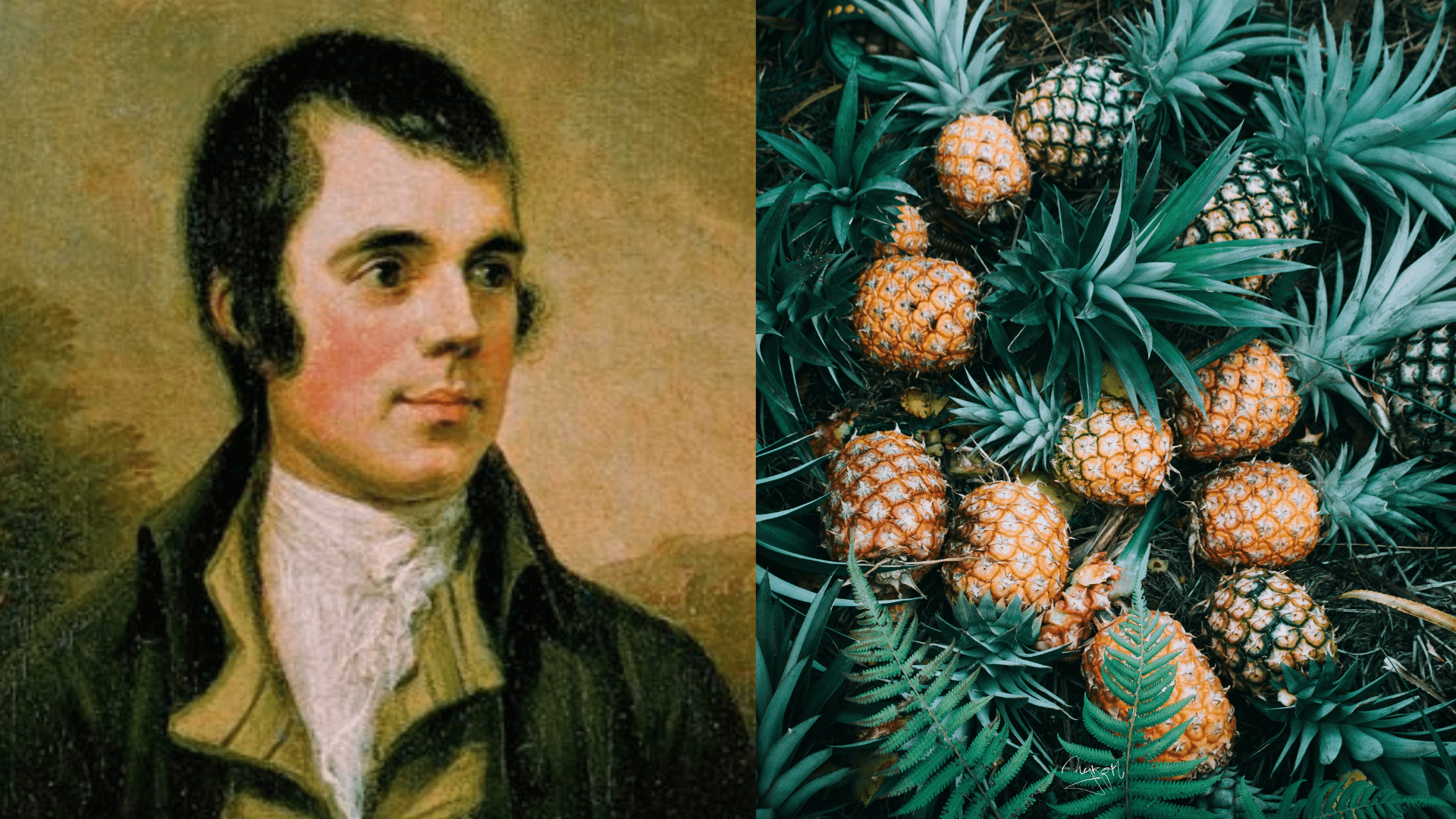

Robert Burns & The Royal History of Pineapples

29th Sep 2022

By Naomi, Mercat Storyteller

'Farewell, old Scotia's bleak domains,

Far dearer than the torrid plains,

Where rich ananas blow!'

These lines are extracted from The Farewell, published in the 1786 Kilmarnock Edition of Robert Burns’ poems.

The reception of these printed verses encouraged Burns abandon schemes of emigrating to the Caribbean and to remain in Scotland. The following year, he arrived in Edinburgh. Around the world, Burns’ poetry is synonymous with a love of Scotland, with Burns opening The Farewell with an expression of how dear the country is to him.

However, in 1786, its domains were bleak indeed and many Scots were seeking employment as overseers and administrators on plantations worked by enslaved labourers, as the wages of emigrants promised to be higher than those for similar opportunities in Scotland. The fortune Burns sought to gain by leaving Scotland for the Caribbean is represented by the ‘rich ananas’ – the pineapple.

A Short History of The Pineapple

The word ‘pineapple’ first appears in the English language in 1664 but the fruit is known throughout the world as ‘ananas’.

‘Ananas’ derives from ‘excellent fruit’ in Guaraní, the language of the indigenous population of Paraguay, where the fruit originates. Indigenous people cultivated the pineapple across the Caribbean, Central and Southern America. The word ‘pineapple’ first appears in English in 1664. Christopher Columbus did not ‘discover’ the pineapple in 1496, but he is responsible for the European veneration of the fruit that followed.

The only pineapple to survive transportation to Europe in the 1490s was received by King Ferdinand II of Aragon (now part of Spain). Philip the Martyr (who tutored the King’s many children) recorded this description: ‘It is like a pine nut in form and colour, covered with scales, and firmer than a melon. Its flavour excels all other fruits’.

The ‘rich ananas’ Burns describes refers to more than the taste and texture of the fruit – its golden colour, its gem-like gleam and the parallels drawn between its leafy top and royal crowns transformed a food of regular consumption of the indigenous populations into a luxury item, symbolising wealth, prosperity, and power in Europe. Indeed, the challenges of transporting pineapples in the sixteenth century, and the cost of cultivating them (approximately £7,000 in modern money) throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries meant that it was considered wasteful to actually eat a pineapple in Europe.

Pineapples & Royalty

The royal association with pineapples as artistic ornaments and table decorations is emphasised by the absence of any such motifs in art and architecture dating to the Cromwellian period.

Oliver Cromwell had defeated Charles I and arranged his beheading while Charles II was exiled in Continental Europe. The Scots crowned Charles II at Scone in 1651, years before the official restoration of the monarchy in 1666 (you can hear more about this on some of our history tours).

Charles II nicknamed the pineapple ‘King Pine’ and commissioned a painting of himself being presented with a pineapple by his gardener John Rose in the 1670s. This was heavily significant, especially following his long exile and the Protectorate of Cromwell. Representing his divine right to rule, Charles also used the fruit to dominate international negotiations.

In 1668, Charles ordered a pineapple from Barbados to be put atop a fruit pyramid during a tense visit of the French Ambassador. The island known to the indigenous population as Liamuiga, had been renamed Saint Christopher Island (Saint Kitts) and partitioned by the French and English colonists, who repeatedly fought over land for sugar-plantations worked by enslaved peoples. The island is now the Federation of Saint Kitts and Nevis.

Charles II presented a pineapple as the central feature of the negotiation table to intimidate the French Ambassador. Pineapples, colonial racism, and political satire are brought together in an eighteenth-century jug recovered from The Blair Street Underground Vaults which you can see after our Vaults tours.

The green porcelain jug is on display within the larger glass case, set into an old fireplace within the historic fabric of the tenement that is now the reception. Believed to depict a satirical statement about the Hanoverian monarchy of the late-eighteenth century, the spikey top and curved body of a pineapple can be seen positioned in a bowl between the satirical characters. We acknowledge that this scene has racial connotations and it is displayed to recognise the colonial past of Edinburgh and the South Bridge where we conduct our tours.

We hope you liked learning about the interesting historic links between royalty and pineapples. If you would like to learn more about Edinburgh and the history of Scotland you can book a history tour with our accredited Storytellers. Don't forget to sign-up to our newsletter too, for more blogs like this one.