Edinburgh Tours, and the Secret Lives of Taphophiles!

26th Mar 2021

Mercat Tours Storyteller Lauren discusses the often forgot about places in which many stories are waiting to be told... graveyards.

I was speaking to a friend of mine recently about walking. We've both found ourselves going on more walks than average over the last year, for reasons I'm sure need not be specified. It turned out we had similar taste in hiking destinations: a couple of hills; a few nice woodland paths; our local historical graveyards.

A few months back, a wonderful book called A Tomb with a View by Glasgow-based journalist Peter Ross introduced me to a new word: ‘taphophile’, a lover of graves.

There’s more of us than you might think, too, and I reckon the number is increasing

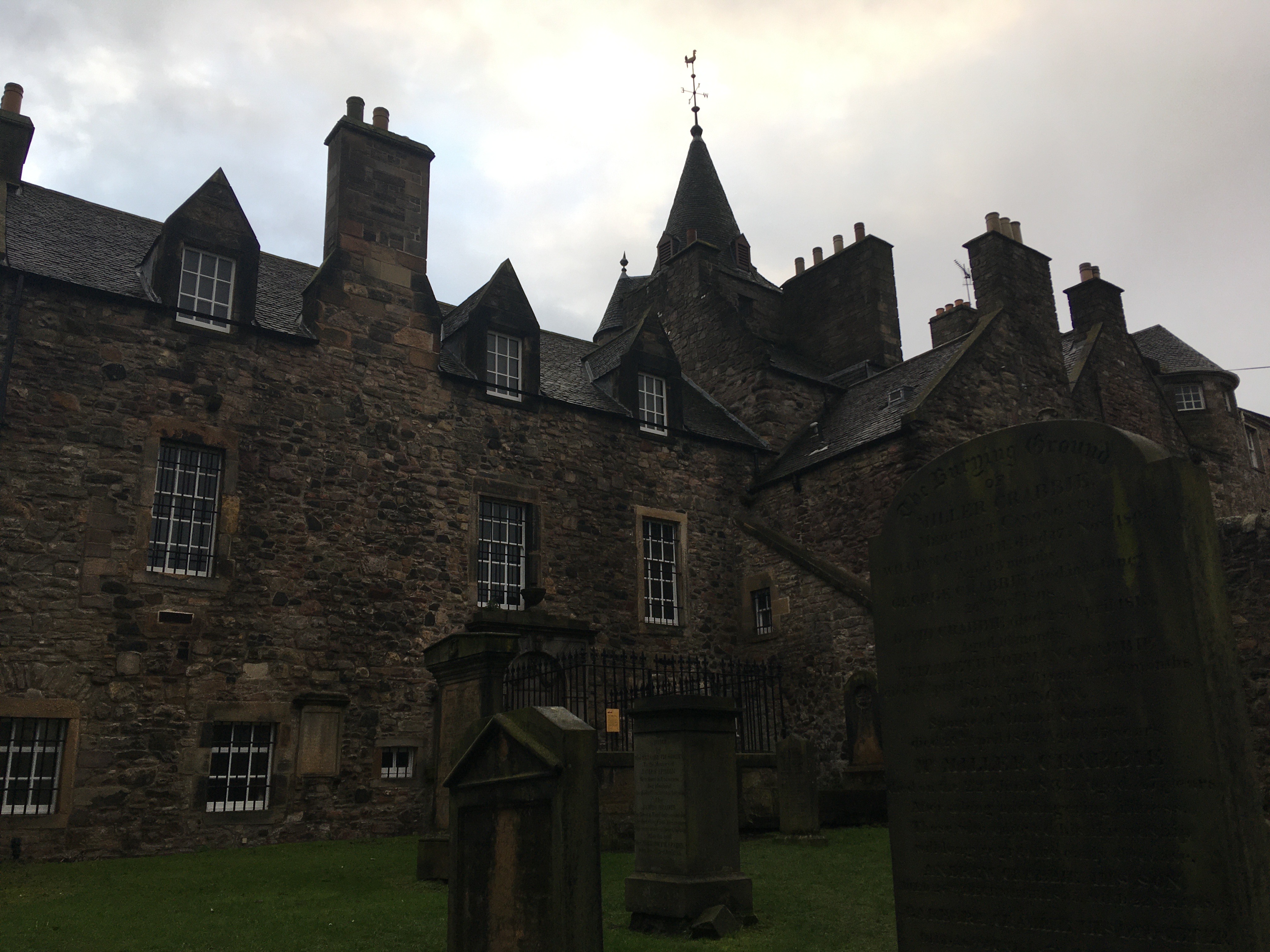

I'm speaking anecdotally here, but it seems many people have embraced graveyard walking in recent months. I support it wholly. An old graveyard has many things going for it as a place to stroll, especially in the age of social distancing. It can be a beautiful space when properly looked after.

It's nice and quiet, for one thing; for another, even those cemeteries ravaged by time command a sort of quiet respect that lends to a very serene atmosphere. It’s free to visit. And that’s before you even get to the architecture: people have come up with some stunning headstone and tomb designs over the centuries, and while many are a tad same-y (urns? On a Victorian headstone? Groundbreaking), you do find some lovely, unique craftsmanship from time to time.

Cemeteries are an interesting blend of human design and complete natural takeover, which – not to get too deep about it – may help to explain both why we like them so much, and why we find them so creepy. It’s a bit uncanny.

When I go for a walk in one of Edinburgh’s many historic graveyards – and there are many – Canongate and Warriston are two of my favourites. The best part is pausing to read the epitaphs. That’s what most of us like best, I think. It’s a bit like people-watching without the nosiness (no judgement. I do it all the time). Reading a centuries-old epitaph offers us a brief, pretty surface-level, but often quite poignant connection to these humans past.

There’s at once a lot you can gleam about someone from their headstone: their job; their social status; how popular they were in some cases. There’s also a lot you can’t, like whether they were any good at their job, or whether their friends actually liked them all that much. In some cases, such as where the headstone bears a famous name, you can research these things. In most cases, the graves belong to ordinary people like you and I.

Perhaps all that’s left of them, centuries later, is that inscription in that stone and the bones underneath it. Our imaginations have to fill in the blanks. In that sense, graveyards are full of stories, both real and imagined.

I enjoy exploring old graveyards for much the same reason I enjoy storytelling; particularly factual stories from history, and especially stories of lesser-known people.

It’s easy to look at our ancestors as the ‘other’

They’re figures that exist more as concepts than as people. We tend – and could you blame us, really? There’s billions of them – to lump people of a particular era together, and sometimes we’re not very charitable to them and their strange ways.

When we tell stories about these people, we’re individualising them. When we individualise them, it’s a lot easier to recognize the fact that we and our ancestors are actually pretty similar. After all, some of us quite literally wouldn’t be here without some of them. I bet there were even gaggles of taphophiles meandering through their local graveyards hundreds of years before the word existed.

People don’t change much from century to century, it has to be said. That’s why we keep being told to learn from the past. We’re too damn stubborn.

For every name on every old headstone, there existed a person who experienced highs and lows and dramas and triumphs in the same way you and I do. If every human life is like a book, a graveyard is like a library – albeit an ancient and weatherworn one. There are countless stories in there, even if we sometimes have to fill in the blanks ourselves.